Folkingham House of Correction

The idle and disorderly

The House of Correction shares the site of the once great castle that dominated the village of Folkingham in the Middle Ages. Such local prisons were originally intended for minor offenders – mostly the idle (regarded as subversive) and the disorderly. Folkingham had a house of correction by 1611, replaced in 1808 by a new one built inside the castle moat and intended to serve the whole of Kesteven. This was enlarged in 1825 and given this grand new entrance. In 1878 the prison was closed and the inner buildings converted into ten dwellings, all demolished in 1955.

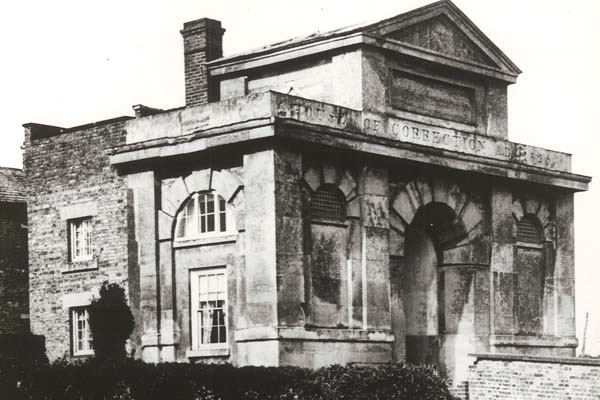

This grand entrance alone survives. It was designed by Bryan Browning, an original and scholarly Lincolnshire architect also responsible for the Sessions House at Bourne. It is a bold and monumental work, borrowing from the styles of Vanbrugh, Sanmichele and Ledoux. Apart from cowing the malefactor it was intended to house the turnkey and the Governor’s horses and carriage. Now it gives entrance only to a moated expanse of grass – a noble piece of architecture in a beautiful and interesting place.

Once the gateway to a prison

In 1982 the House of Correction was acquired by the Landmark Trust, a charity which rescues historic buildings in distress and gives them a new life by letting them for holidays. Its previous owners were Sir Arthur and Lady Petersen, who had rescued the building from demolition in 1965. By passing it on to Landmark, they both gave it a secure future and also ensured that it would be appreciated by all those people who now stay in it. Like many buildings cared for by Landmark, the House of Correction as we see it today is a fragment of a much larger building.

There had been a House of Correction in Folkingham, serving parts of Kesteven, since 1609. This original building, now two houses in the market place, had four cells and a small yard for exercise. Here, in a system devised by the Elizabethans, the ‘idle poor’ were confined and put to work to teach them better ways. But while the corrective power of hard labour lay behind the original Houses of Correction (also known as Bridewells after the first to be founded in a former royal palace in London) they soon merged with ordinary gaols or lock-ups. This is what the one in Folkingham had become when it was visited by an inspector in 1774. His report was damning: as not only was it damp and cramped, but there was no pump and no sewer. When another report of 1802 told the same story, plans were made for its replacement.

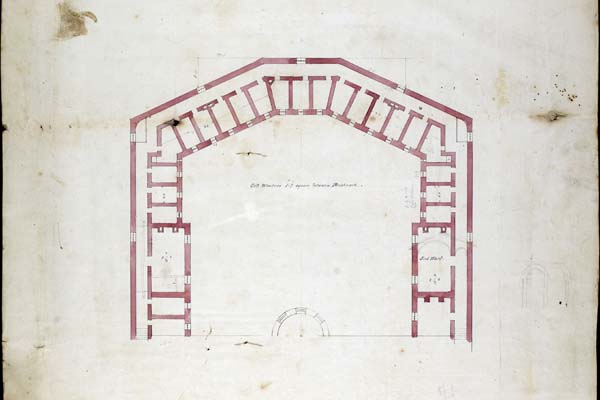

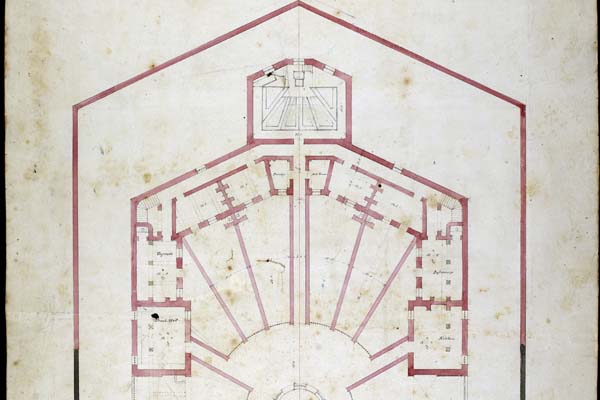

Work began on a new House of Correction in 1808. It was built on the site of the great castle of the de Gaunts and the de Beaumonts, which had been abandoned since the 16th century. The moated inner ward lent itself exactly to the new strongly walled compound. The entrance seems to have been quite humble however - an opening in the brick outer wall with the Turnkey’s lodge just inside. The Governor’s house lay beyond that, on the far side of which was the airing yard for the prisoners, surrounded by the prison buildings themselves.

An 18th century writer declared that prisons should be depressing by reason of their function, with civil prisons expressing misery while criminal ones should evoke actual horror 'let there be deepest shade, cavernous entrances, terrifying inscriptions.' The first entrance apparently did not get the message across strongly enough. In 1825, a gifted local architect, Bryan Browning, was commissioned to build a new gatehouse. Browning had clearly studied neo-classical architects such as the Frenchman Ledoux, who published designs which were full of strength and drama. He was no doubt familiar too with the work of Vanbrugh, particularly his military buildings. As this gatehouse shows, Browning had undoubtedly learned how to give power to a design by the use of mass and form in a way that must have sent the hearts of new inmates plummeting into their boots.

The regime inside was still based on the original lines of reform through hard treatment and hard labour - a short, sharp shock. Bare boards to sleep on, bread and gruel to eat and work at a treadmill or stone-breaking were standard for felons undergoing a short sentence. Women worked in the laundry or picked oakum. For all there was a daily chapel service.

The House of Correction closed in 1878. Two years later it was sold to a builder who pulled down the outer wall and turned the prison buildings into cottages. In the 1930s the gatehouse was also turned into a house, when a brick addition was made at the back. In the 1960s the cottages were declared unfit and were demolished. It was only by the intervention of the Petersens that Browning’s monumental gateway did not suffer the same fate.

For a short history of The House of Correction please click here.

To read the full history album for The House of Correction please click here.